The State of Entrepreneurship in Canada with Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf, Co-Founder and CEO at Flinks

Download MP3Neo S04E31_YG_v2

===

Jeff Adamson: [00:00:00] Welcome to Behind the Brand, the podcast that explores how technology, innovation, and other forces of change are reshaping age old industries and giving rise to new opportunities. Join me, Jeff Adamson, one of Neo Financial's co founders, and an awesome lineup of guests to discuss how the world is evolving to meet the needs of customers.

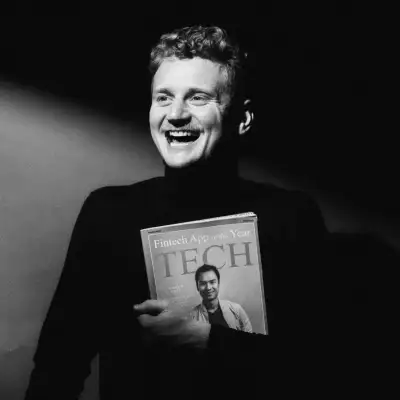

In the next few episodes, we're focusing on the financial industry. In Canada, it's the UK. This is a space that has been dominated for decades by the big five banks who hold 93 percent market share. There's an incredible number of opportunities for innovation in this space. On this episode, I'll be speaking with Yves Gabriel Laboeuf, or as I call him, YG.

YG is the founder and CEO of Flinks, a company that develops tools that turn raw banking data into actionable insights. In 2021, National Bank took a managing share of Flink's with a 103 million investment, which included 30 million in [00:01:00] growth capital. YG is on a mission to accelerate innovation in the banking and financial services sectors.

And we have a great conversation about YG's experience as an entrepreneur, his view on open banking legislation and the competitive landscape in Canada. So maybe, maybe just to start out YG, tell me a little bit about where you grew up. Kind of your story getting to kind of the founding of flex

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: so i actually i i was born in montreal but i um my parents moved to get snow so it's right beside ottawa when i was four or five my dad is a lawyer my mother is uh i don't know how to say that in english actually it's like a it's like a teacher but uh for kids and difficulties.

So really like academic background, school was important growing up. And for me, that was just no fit. Like I remember my first year in elementary school, we were like, like reading a book out loud. Uh, and my teacher telling me like, Hey, you're not following. And I'm like, yeah, I don't like this story. So it's just like, [00:02:00]

Jeff Adamson: your dad have his own firm.

Was he, was he an entrepreneur as a, as a lawyer or. Was he working for kind of one of the bigger firms? No, he

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: was for a government of Canada. So he was, uh, for a while at the private council, uh, and then at war crimes and then, uh, for, uh, environment Canada at the Canadian, Canadian environment evaluation agency, something like that.

I don't know what to say in English, but all for the government of Canada. So yeah, like really no entrepreneur near, near me. It was more like. To me, like being entrepreneurs, I guess, uh, first and foremost, creativity, it's like a way for me to express myself. That's kind of how I ended up doing that. But when I was at like university, uh, cause I didn't make it to university.

My, my,

Jeff Adamson: but was that a, like when you, when you were in school, elementary school, we were in high school and then this is relevant for me because I've got two young kids at home. They shouldn't listen

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: to me

Jeff Adamson: though. Well, no, I think it's, and like, you know, my founders, they all have, [00:03:00] Uh, small kids, young families, and I'm always like, obviously, there's so many different paths, but I'm always looking and saying like, Oh, my goodness, it's, you know, my son doesn't listen, but like, I don't think that's always necessarily a bad thing, because I think there's certain people who kind of color outside the lines who don't like the rules, who Mm hmm.

I think kind of have that same feeling that you have where you're like, Hey, I just don't want to do this. I want to do something different. So I guess how did you then, especially because you get kind of swept up in the path of just like, Hey, you need to get good marks, go to university, but it sounds like you kind of didn't feel like that was the thing for you.

It didn't sound like you were going to become a lawyer. You were going to, Get a PhD. But how did you kind of maintain that same level? Because in order to make a company successful as Flink's, I think you have to have a, I think some sort of excellence inside of you. But if it wasn't academic excellence, because you didn't really like school, then how did you make sure that you stayed on the path?

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: I mean, that's a good question. And I myself have three young [00:04:00] kids as well. Two beautiful boys, four and a half, three and one and a half. Oh, wow. Very young. So you're in

Jeff Adamson: it. You're in it with.

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: Yeah. I'm not sure how I feel, uh, when they'll listen to this podcast, but, uh, I guess to me like school is the, like, it's the happy path, the easy path, right?

So it's, if, if, if you like school or that you're good at school, then I think like that's like, that's just the way that the path you should take. School to me though, is kind of a mold, right? You either fit in it or you don't fit at all. And I was considering myself someone that didn't fit and it's probably a super complex algorithm, but one of the thing that for me was striking when I was at school and precise, like.

Most, most importantly, when I was at university is, I guess, a small problem with authority where some teachers were teaching me things that they haven't gone through, like for business classes, by example. And I had a problem [00:05:00] listening to them for that reason, or I did some, uh, some classes in engineering, like computer science.

And the programming language that they were teaching us is the one that the government of Canada is eager to hire people for. But, like, that's a, to me, that's a massive lack of ambition, right? Like, we want to solve world class problems. Uh, why are we even learning that programming, uh, language? So I think, like, looking at my kids growing up, what I want is, for them, of course, to have like as much love as possible from their parents, but also to have, uh, an openness in the different paths you can have other than school.

Because to me, school was really not a good fit. So yeah, it's, it's, it's, It's easy to say when you're not into it, uh, and it's hard to think of the different path than school. But like an example is I've always liked planes, right? And you can become a very good pilot [00:06:00] without going to school. Um, so yeah,

Jeff Adamson: well, I think it doesn't convey the same benefits that it did, you know, when our parents were growing up and.

You know, I'm probably a few years older than you YG, but I think our parents are probably roughly around the same age. And, and, you know, my, my father never went to university. I think he kind of got through high school. My mom did, but I think she was the only one in her family who got a degree. And I think it's kind of like the advantage that you have now versus that you had back then is totally different because it's kind of like, if you're all, if you're all in a stadium trying to see the event and everyone stands up, You don't get a better view and I think that's kind of the, the situation that we're in now where it just seems like so many people go to college, you get some sort of education, people, there's a lot of people coming to Canada who are already educated as well.

And I think you're starting to see a lot more success stories of people who obviously like the famous dropouts of college and I think people are starting to value the experience they're getting in different [00:07:00] types of work environments versus before it was like get a degree, go work for a big company, stay at that company for 30 years and then retire.

That's no longer the path that people think about. It seems like,

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: and I think that's fine. Like, I think, um, looking at like, uh, lawyers, uh, in private firms or like, uh, like managers in, in large, uh, large companies to me, it really sucks. Like those jobs are hard. They require a lot of time and you're kind of like ending up, ending up being like a copilot selling your hours for a paycheck.

Right. Uh, which I guess like most people do in some way, but to me, it's not, it's not a way of living. Like I can't, I can't tolerate that.

Jeff Adamson: I, we had, uh, we had Mike Murchison from ADA on the podcast and he, to me is also similar to you were very clearly wanted to be an entrepreneur. He started multiple companies.

At what point did you say, Hey, like working for a big company isn't for me. School isn't really for me. I want to be an [00:08:00] entrepreneur. How old were you when you made that decision? Or was it even a conscious decision?

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: Like, you know, there's some people that actually want to be entrepreneur, want to like build something and be proud of it.

And I wasn't like, I wasn't like that. Like it wasn't about like being an entrepreneur. It was about like, really like getting those creativity outside my head to businesses ideas. And I was testing things all the time. Eventually, actually, I started the e commerce bike parts because I was really into cycling.

So like that was easy for me to do. I knew the distributors. I made deal with them. I was probably like 22, 23. I started distributing a brand called State Bicycle, which was really cool back then. It's like fixed gear. And when I first launched that on my website, I made like 12, 000 in like two, three weeks.

Uh, which to me was incredible, like in the basement of my parents, but the margin were very bad, so I thought like, Hey, how about I become the distributor of that brand for Canada? So I reached out to [00:09:00] the company and I'm like, Hey, I want to distribute your brand in Canada. I drafted like a distribution agreement.

Uh, with like royalties and so on. I like all by myself. We had, didn't have JGPT back then. So I found the agreement like a two, three years ago. It's like poorly written, but they agreed to it. And I actually, I lied on my age, on my background and so on. Cause like, there's no way I would have signed that when I was 22 years old.

Like. Who the fuck is that kid? Right. So, yeah, so I did that and that to me was like, all right. It's like, you, you, you can really like do whatever you want, right? It's it's, that is business, right? You, you take the path you want. Um, eventually we started like, uh, manufacturing bikes in China. Uh, we like, uh, created a brand called Moose bicycles still, still exist.

So like, to me, that was like a, some sort of aha moment of like, all right. It's really like when you decide to do business. It's like deciding on doing anything of your career, except there's [00:10:00] no like actually requirements. You can really do whatever you want.

Jeff Adamson: When you think about the reasons why people start companies, like, and I'm sure you have lots of aspiring entrepreneurs who talk to you and want to learn about how you did it.

What do you think some of the wrong reasons to start a company are?

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: Well, one thing to be an entrepreneur is a bad reason to be, but the other, the other one is, um, starting something out of an idea. Like people always say like, uh, Hey, I have this idea. What do you think of this idea? Whatever. I think like, it's very easy to say for probably like people like you and I, but like you should start out of a problem more than an idea.

Right. And it perhaps won't push you to create. Precisely what you'd like to create, but I think, I think started starting a company is about finding momentum quick. And from there you can actually iterate in the direction you want. Right. Um, so as soon as you have like a bit of revenues, a bit [00:11:00] of clients.

From there you can go in the direction you actually want and deliver on your vision. Um, but just as like Musk did it with Tesla, it's like sometime you have to seed your company with like this one specific product for him, it was like the roadster. So sometime you got to find your, your Tesla roadster to seed your vision.

Uh, so I think like, to me, if you start out as a problem, ideally a big problem, I think you're on the right path.

Jeff Adamson: So what was the problem that you saw before starting Flink's? What was the, the kind of opportunity as you saw it at that time, because that was what, 2018?

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: So we incorporated in 2016, late 2016.

Uh, but we like, we more officially started like coding links in 2017. I had the software engineering company with two great partners. Uh, we had a, an office in, uh, Northern Thailand, uh, Chiang Mai. So most of the engineers we had were in Chiang Mai. And ultimately what we were doing is like developing for marketing agencies.

[00:12:00] So like most marketing agencies say they have like in house developers and that they build their websites internally and so on. We were one of those companies that actually was behind the scene, actually doing the development. Um, in some occasion we actually had even like email address of those marketing agencies.

So

Jeff Adamson: they'd outsource it to you and then you'd outsource it to Thailand? It

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: wasn't outsourcing cause we were three, uh, partners, right. And one of them was actually living in Thailand. Uh, but yeah, they were made in Thailand during the night and the next morning we had like, whatever. Um, and at some point we started working with lending companies and some of those lending companies wanted us to integrate with financial data providers.

So they had found something, a company called Decision Logic based in San Diego. So we integrated with that and the reliability of that solution to access financial data was really, really bad. So we actually flew in San Diego to meet with them and tell them like, Hey, like, what's up? Like you have a very nice product, but.

Like if it doesn't work 50 percent of the time, it's so [00:13:00] expensive to attract leads on the website. We've got to find a way to make it work. And they told us like, yeah, we're just reseller. We use like two provider, Finicidi and Yodli behind the scenes. So we're like, okay, we'll go and work with them directly.

We met Yodlee back then, which was like, uh, by far the market leading solution. But we also bumped into a company called Plaid back then, uh, which was like 20 employees. Uh, we reached out to them and we were like, Hey, are you coming to Canada? And they were like, no distraction, not coming to Canada for now.

Uh, so we're like, okay, well, we'll work with the legacy player Yodlee. Uh, so we integrated Yodlee, still extremely bad, super expensive, ugly customer experience. So we're like, we like what Plaid is doing, but we wish they were in Canada. So we're like, how about we actually start building the same thing that they did, but in Canada?

So we reached out to a couple of companies, um, that we thought would be interested in using, uh, in using financial aggregation. Uh, and we were able to get about, I would say, 1 million [00:14:00] AR of letter of intent of like really non binding, just like small letters saying like, yeah, we have this volume, we'd be interested in using a solution.

And that's how we started. That's how we decided to start a company.

Jeff Adamson: How hard was it to get that first letter of intent? Did that letter of intent come even before you started building? Or was it like, were you basically selling the vision first? Yeah,

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: that's actually like a very safe way that we approach building companies, uh, where we want to test the market before even incorporating the company, right?

Um, so for Flinks, we got those letter of intent before incorporating the company. We didn't have any problems really getting those letter of intent. The only company I would say that was a problem and he's going to laugh because he's a friend, but it's a, it's Tate at Zezun. Uh, maybe, you know, Tate, I'm actually, uh, I'm hanging up with him tonight.

Actually, I'll tell him, I say, hi, as far as I remember, Tate was really hard to get a letter of intent from, uh, so never, never got a letter from him. [00:15:00] But other than that, it was fairly easy because it was like non binding and ultimately what I was telling is like, Hey, imagine a world where like we're the best provider, super reliable, would you use that?

Yes or no? And if yes, like what's your estimated volume? That's it.

Jeff Adamson: Got it. Okay. And so then, then you went out and raised capital on that kind of, I'd say vision of building flinks. And you're basically saying, Hey, we already have fit here. Or did you wait until you got those clients live and then you raised?

So

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: raising at Flink's was like for the seed round most, most, uh, particularly was like a love hate relationship. Like it was really hard. I cannot point at like one specific reason, but I think there was like fundamentally a misfit between the way we operate. And the, the way VCs traditionally think about building a company, uh, maybe to backtrack a little bit after we got those letters of intent, we raised cash, but for, from friends and family, so we raised like 300, 400, [00:16:00] 000, which ultimately was enough to pay for the first version of links.

But I remember like in July, July, 2017. Uh, we had a like product, not super good. We had like a couple of clients, but we also had, uh, three weeks left of runway. So, uh, at some point we decided to start posting every morning on Slack, how much cash there was left and how much we were burning today. And the idea was that like, we got to light up a fire under her ass.

Cause we got to find a solution to either grow revenues or bring more cash from investors. Eventually we had no choice, but to get back to those, um, angels and ask them for more cash. So we were able to, I think, get like an additional 300 or 400, 000 and started, uh, raising the seed round. I would say like Q3, 2017, right after we got that cash.

But it was really, really hard, like really hard. Like the, the, [00:17:00] they say you get, you get, uh, you get no from like tens of investors, but we got, we got that no from like hundreds of investors. Like nobody wanted to fund us except one, which perhaps we should have take, uh, took the money from, but it was a real ventures orbit fund.

Like they're like, uh, precedence seed stage, uh, fund. Uh, and they wanted to invest like half the cash we wanted. We wanted 2 million bucks and they were proposing a million bucks. Uh, and they said like, we're putting a million bucks. We can close super fast, like no bullshit, super easy. And we're like, Nope, we want 2 million.

And so we said, no. And then, and that was probably like October, 2017, and we ended up closing the seed round in June. So for 1. 7 million,

Jeff Adamson: oh my goodness, that's a long fundraising cycle. It is. You said something when we first met, and that is one of the things we do in Canada that works against us is we try to raise on results, not on [00:18:00] vision.

Explain that more to me. I think that's really interesting.

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: So like both startups and VCs like to talk about results and see the results. And I think, like, there's a thesis to be made where if you're building toward a, like, multi billion dollar market, you shouldn't really care about if you're at, like, 500K ARR or 700K ARR.

But fundamentally, like, the experience we went through, uh, was that Everybody was actually like caring quite a lot about the precise amount we were at. And on the flip side, it's what we were, um, pushing forward. Like not the vision at all. We're like, we didn't have a vision actually. We were like, yeah, like we're just opportunistic, right?

Like there's a problem. We're growing the company. We're going to figure it out down the road, like what we're going to do to like scale the company. But like, right now we're solving that problem and see like how much revenues we have. I don't think that's the right mindset to have, but I don't see that there's a different mindset to have [00:19:00] when you're raising in Canada.

I don't have any experience raising in the U. S., so perhaps it's the same or perhaps it's completely different. I am close to some VCs in the U. S. Uh, and to me, it seems that it's not the same, but still, it's like, I think as Canadians, uh, and as part of the Canadian startup ecosystem, we're like, it's hard to see a world where like, we get massive amounts of success from several different companies, different startups.

When we keep investing in results more than vision, because again, to me, like the results Like when you're at least a later stage, like you should care about results, but when you're at such a nerdy stage, like you can look at them for market traction, uh, validation or whatsoever. But yeah.

Jeff Adamson: Listen, like when you said that, it actually stuck with me.

I thought about it a lot because I was like, man, cause it's so true. And especially even, even what, what stage NIO is at where. You know, we've raised a series C and so now we're, we're basically at the stage [00:20:00] where you're like, okay, looking at, you know, going public profitability, things like that. But I think if you're, if you're only raising off of results, you're just commoditizing yourself against all the other results out there.

But vision is completely differentiated because everyone's going to have a different vision for their business. Yeah. Yeah. I think the reason why it stuck with me is because I think in Canada, I think it happens a lot and I think we often start companies in Canada that are focused on Canada, some people like, for example, the Zezune guys, and I think there's a couple, there's a number of them now, but they'll start in Canada, but they're focused on the U.

S. market, but I think that's less common than people starting companies in Canada focused on Canada and then you're basically trying to sell the vision of Canada and relative to the selling the vision of, you know, being number one in the U. S. It's a 10 times larger market and you just don't hear that many Canadians saying, Hey, we're starting in Canada, but we're going to be a global superpower in this industry.

And I really hope that as Canadians, we can start beating our chests a [00:21:00] little bit more and really kind of saying like, Hey, we're not actually happy with third or second place anymore. Yeah. We actually think that we're just as capable as our U S counterparts. In fact, a lot of the amazing companies in the U S.

Are actually Canadian founders instacart. I think you've got a slack. There's a, there's actually a number of these. Like, I call them like stealthy Canadian founders who have just kind of left Canada behind, but obviously have Canadian roots. I mean, maple, vc, uh, Andre true. He invests in companies that have Canadian roots.

I want these people to, to stay and have the value creation happen in Canada. Because frankly, I don't, I don't think Silicon Valley really needs any more help. I think they're doing just fine without us. I think they know, you know, if all the Canadian founders stopped going to Silicon Valley and started their companies in Canada, I don't think Silicon Valley is going to miss them.

I think that, but I do feel like it has an impact on Canada though. If we could have started Slack in Canada, If Slack was headquartered in Canada or if Instacart [00:22:00] was, uh, or even Garrett camp with Uber. Yeah. If that had been headquartered in Calgary where he's from, I think the Calgary ecosystem, I think the Toronto and Vancouver, Montreal ecosystems be, would be totally different.

Transformative. Like if Uber, imagine if Uber were headquartered in Calgary, what that would mean. That'd be crazy for, yeah. . Yeah, it's, it's even hard to even imagine that happening. But there is a world where we, we keep people like yourselves in Canada. Building global companies and you just, we need to have a culture shift in Canada, where we're looking at the things that you're doing and the things that others are doing and celebrating the success.

Cause I mean, doing what you did that early on, like you basically started up when Plaid had 20 employees building a competitor to Plaid and how much money has Plaid raised a lot,

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: like hundreds of millions, fun story. Actually, when we, uh, like the, the. Yeah. I think a month before we closed the seed round or maybe like two, three weeks before Plaid announced that they were, um, opening up in Canada.

And I remember like literally like a [00:23:00] couple of weeks before closing the seed round, uh, which we've worked on for eight, nine months. Right. And I got a call and back then you were at like maybe a million ARR back to like raising on results, like doing a seed round at. Eight, 8 million pre money at the million dollar ARR.

Like, you don't, you don't see that often. Right. But that, that was us. And I remember getting a call from one of the VC participating in the round, telling me like, look, we're going to do the round anyway, but good fucking luck, like you guys are dead. Like that is coming, like, that's it, that's done, like done, like, and I was like, like super frustrated about that because, and I couldn't point out precisely why, I guess it's like, it gets back to like the lack of ambition of Canadian companies.

Having competitors is fine. It's actually good. Uh, like it keeps you sharp. Right. Um, and you're gonna, you gotta find ways to like, have the right product that fits in the market against your competitors. But ultimately [00:24:00] like for us, we were like, again, one of those us companies scaling in Canada, thinking they're going to steal all of the market.

Platt, I don't know how many head of Canada has been since the, the first announced that they were scaling Canada, but before Platt, there was Finicity trying to win the Canadian business. Uh, there was Yodlee trying to win Canadian businesses as well. And there it's just, it's, it's such a hard market. Uh, to be in, cause it's so small yet so big from several different point of view, um, that, uh, yeah, like it was, uh, it was a special moment when we got that call.

Jeff Adamson: How did your team react to that? Cause I think there's, I think it does help having a big, scary competitor. I know at Skip, when we first started up, uh, Just Eat, which was a global superpower, also launched Canada and then Uber Eats launched their first market in Toronto, And then DoorDash launched their, their first international market in Vancouver, and then we hadn't [00:25:00] even raised a dollar of venture capital.

And I think they had already raised, you know, billions of dollars of this, you know, massive war chest to go against us and at least how, how we're wired in, in kind of the, the teams and in the culture we've created where we like having kind of a public enemy number one, because I find that that's really makes it easier to rally your team around that.

Yeah. And it makes kind of winning feel a lot more important, but how did your, how did your teams in terms of the culture that you've created within Flinks, how do they react to Plaid coming to Canada? And then just more broadly, like what kind of culture do you like to create within Flinks?

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: I mean, that's a good question.

As far as I remember, like we were shielding any other teams than sales from like those concerns we had. Yeah. Um, and precisely engineering, it's like, as long as the division was like, as long as you guys deliver what we tell you to deliver, we're going to win. If you guys just focus on that, just like, think about that.[00:26:00]

And we're going to like focus on like signing more deals, making the clients happier and happier and so on within the sales team. One of the challenges that we faced. against competition in general, was that like in the very specific, uh, market segment we're into, clients care about how you access the data, but fundamentally there's only way to access data pretty much in Canada, at least back then.

And there was a lot of lying, like provider, providers lying about, you know, Uh, how the excess data, uh, saying like, uh, Oh, there's API APIs and so on. And we just didn't feel comfortable lying about that. And frankly, we were like, even though we would have said that, like, it was not credible for us because we were way too small.

Like there's no way we're integrated with banks and so on. So we, we had a hard time staying like, I would say at some point competitive by keeping the same story we had. But ultimately what we decided to do from a strategic standpoint is like, we're just going to focus on having a good product, like the best product there is.[00:27:00]

If companies actually decide to move forward with a competitor, our assumption is that it's going to be the same story as what happened with Yodlee and Finucity. People down in the U. S. are focused on winning in the U. S. And Canada is often time and distraction. And it was hard at some, like, at some points to see some clients or us losing clients.

We actually lost one of the top 10 banks in Canada because of that. We're like, just, we're just going to like stick to what we have, be honest. Um, and, uh, they decided to choose another provider and they actually came back 18 months ago saying like, yeah, like quality is an issue. So like that, that's, that's for us is like testimonial of a winning strategy that takes time.

But yeah, like, I mean, internally, we were scared when we were seeing like the massive fundraise or like the visa deal out on, I don't know how many calls I got, like, yeah, is it good or bad for flanks from investors, shelters, whatever. But yeah, like there is times when we were scared, scared of like [00:28:00] how big the competition or how funded the competition was.

Jeff Adamson: If someone were to ask you, you know, what's, What type of company is flinx to work at and when you think about kind of building a culture and environment some people will say hey we're all about ownership or hey we're like a real product centric company or you know if you think of the culture that kind of uber had which is kind of like a more of a win at all costs do whatever it takes highly competitive environment how do you think about that at flinx.

And how did that evolve as the company grew? Because I, I understand like when it's just a few people in a university dorm, then you've got like maybe an office. Now you got more people, you got some funding, and then you, you, you have this partnership with national bank where They come in on the cap table as well.

How have you tried to steer the culture as it's changed? You start getting big clients on and now these clients have demands and wanting input on your roadmap. [00:29:00] It just, there's so many of these forces on you as CEO and founder, how do you kind of maintain the culture? But then also think about how does that need to change over time?

Because if you're still operating the same culture, you know, when you're now kind of have this partnership with national bank, you know, versus when you're just a small business, like you just. They're not necessarily fully compatible

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: in flink's DNA. We're like a sales oriented organization, like sales is probably the most important thing at flink's and that's how we were able.

To in a certain way scale fast, but I think it's also a testimony of raising on results because ultimately it's like sign deals and grow revenues at all costs rather than like build the best product at all costs. But I think we, uh, we're successfully transitioning from being a sales oriented organization to being a product oriented organization.

Uh, we're still in the process of optimizing toward that. [00:30:00] Um, but I think one of the realization we did probably like in the past 24 months. Is that for us, the biggest opportunity is to grow within Canada. Like we have a very nice footprint in the U S right now, but growing in Canada is where we see most of hundreds of millions of dollars of opportunity for us.

There's just no clear path for us in. Switching or winning at that, if we keep being a hundred percent sales oriented organization. So we've started that work of like switching to being a product, but that brings me to the other part of your question, which is how is it to work at Flink's? I think like if you're looking for a structured environment, really Flink's is not for you.

Like it's a highly, highly unstructured environment. And we have, uh, uh, Something called the constitution deck, which is a document that we did, I think within the first couple of weeks of links that push forward the, uh, the values [00:31:00] of links, but also some principles, guiding principles that we have internally to me, like one of the leading value that can trend can be translated into some of those guiding principles.

Is the autonomy. And I don't, I don't feel that we've always, always respected, uh, the autonomy value within flinx, but I feel that's really the most important value that we have to respect in order for flinx to, uh, stay successful. And the way for me to see that being, uh, respected within the company is to kind of have a, Culture of intrapreneur where you're kind of your own boss and you do whatever, whatever you have to do to make your team successful.

That's, uh, that's pretty much how it is at the links.

Jeff Adamson: Yeah, that's, that's tough to, to manage too, because I think a lot of people, if it's their first startup, depending on when they joined the company, there's varying levels of clarity they're going to have in terms of what exactly is the thing that they should be working on at this [00:32:00] exact moment.

And as. As an entrepreneur or intrapreneur, you know, you have that autonomy, but then if you also want that direction and that more prescriptive approach that you see in larger companies, larger companies, it's a lot more prescriptive. Like, Hey, here's the exact same exact thing that you're supposed to do.

Here's all the ways it's measured. Here's kind of like how you're going to be bonus at the end of the year. And here's a career path in the ladder that you can climb. And. It's, it's kind of a double edged sword at a startup because you get the benefit of having that autonomy, but you also get the other side of that is the chaos and.

The, the changing in direction. And I think what I love about startups is that people really get to figure out pretty quickly what they like and what they don't like. And, and I think that no one's trying to deliberately like create chaos. It's just the nature of the fact that you're only like six years old, seven years old as a business.

Versus people may be coming from working at a company that is a hundred years old and they've had a lot of time to figure out exactly like, how should things be done? I want to [00:33:00] touch on, on open banking because it seems like it's getting a lot more attention now. It seems like, you know, touch wood, it will happen going to be a federal budget announcement on, I think, April 16th.

And there's a lot of expectation that there'll be. Wording around open banking, the timeline and, and ideally something that has some teeth to it. How does that affect flanks? Like what's flanks role in open banking? And will that change the kind of the future flanks as you think about it?

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: It will change us for sure.

But our vision is that it will change, change us for the best. We've been. probably one of the biggest advocate of, um, open banking in Canada. Uh, we've participated in literally like everything we could, um, in, in any way we could. And what I think, what we're hopeful that will happen is ultimately a democratization of the, well, open banking, like, uh, literally like, [00:34:00] democratization of people being more willing to leverage their bank connectivity to proceed to, by example, uh, open, opening another bank account or, uh, doing a payment or whatsoever.

I don't see a world, uh, really where this was not. To happen in Canada to me, it was like a hundred percent certainty, just like a matter of time. Right. Um, I think we're like ripe to have it right now. What I'm more, more excited about is the different, uh, all of the use cases that we'll see, uh, being created out of open banking.

Uh, and more precisely in payments. I think like the payment infrastructure in Canada, really, it sucks right now. We're like lagging quite a bit. I have a, like a friend that works at the national bank that was telling me that, um, he has a bank account in, uh, in Europe. Uh, I think he's from, uh, Belgium or something, and he had to transfer cash from his, uh, Belgium bank account to his, uh, Canadian bank account.

And it was. Higher than his limits, right? [00:35:00] Uh, so he just got on the app, he approves a higher limit for 24 hours and transfer all of his assets in his, uh, National Bank of Canada bank account, right? And that's it. Like, he just approved the limit by himself. And then after 24 hours, the limit is back to like the normal limit.

Uh, and he was telling me like, how come we don't have that in Canada? Like, it's like, it's ridiculous. It's like their banking system here is like. It's lagging versus like other, uh, other region of the world. So I think like open banking is like a first step toward having a better, uh, banking environment.

But, but truly it's like, if we actually look at like what's in it for consumers and what will actually really happen for consumers, I think, uh, it's a massive opportunity for a lot of people to, uh, move away from certain like, uh, predatorial bank. And I think that's good. I think that's a highly positive.

Jeff Adamson: Yeah. And I think that like, I feel like open banking is really kind of all stake, no sizzle. It's like, it's done a [00:36:00] terrible job of marketing itself. And of course it's, it's, it's, it's not an organization. It's not a. It's a, it's really a framework. It's a way of operating and it's, it's happened in every other market, but we haven't been able to do a good job of making this an issue that politicians feel like they should be driving forward and making it a policy issue.

It's starting to come to the forefront now, I think, because. People seem to be more keenly aware of that Canada's falling behind dramatically from a productivity standpoint like we're just now Canadians are making kind of 70 percent to the dollar of their American counterparts GDP per capita is kind of.

been stalled out or negative for the last decade. And you've got the cost of living as well. And to me, it's like anything that we can do, basically the, the cure to giving customers better service, lower prices, more convenience is competition. That is like the one thing I think that's proven to, to basically give more value to, to consumers is having competition and open [00:37:00] banking to me, even for example, um, payments, modernization with real time rails, These are just things that are just going to blanket increase the level of competition in Canada.

If you can make it easier for people to say, you know what, I had a bad experience with bank a, I want to go to bank B now, and I want an easy button to do that open banking makes that a reality to do so therefore if you're bank a, and you know that this customer is one click away from moving to someone else, like if it's as easy as.

Actually, for example, like changing telecom providers is shockingly a lot easier. Like I switched, I switched away from kind of the one I had for a long time and I was like, finally had enough. And so I finally, finally switched over to a partner of Neo's at public mobile. And I was like expecting, I like cleared my schedule for like half the day.

I was expecting to have to like jump through all these hoops. Maybe you have to drive across town, prove my identity, everything. And they're like, no, no, no, we're just going to send you a text. You just click on it [00:38:00] or like reply with yes. And then everything just gets moved over. I literally was shocked at just how easy it had become and banking, I think, has the promise of being that easy, but it's never going to be that easy if we don't start kind of forcing the banks to adopt some of the modernization that is already commonplace years and years ago in other countries.

And I think like Flink's is going to play, I think, an instrumental role in that, that future. I think you guys already have a lot of the infrastructure in place. Like, how do you think. Flink's is going to support that transition to the open banking environment.

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: Well, um, I mean, a couple of years ago we built a product along with national bank, um, called outbound.

Um, and ultimately it's like an out of the box solution for financial institutions to distribute their data. What we see right now is that most of, most of the large financial institutions probably already have the capabilities internally to distribute their data. And they're like questioning themselves on two things.

The first one is. Do they actually want to distribute their data? [00:39:00] And right now, so far, the answer, the answer has been no. But then if that switch to yes, either from regulations or from a commercial incentive, how do we actually distribute that data? Right now, I mean, Flink's Has hundreds of clients in Canada are banks equipped to handle hundreds of integrations with hundreds of different platforms and managing all of the tickets to help the integration, the billing and so on.

I think they don't want to do that. And I think, uh, way we've been positioning flanks is to be that last mile delivery because having about, I don't know, like 80 to 90 percent market shares in Canada and financial data distribution, we're like literally, uh, one stop shop solution for that last mile delivery.

So we handle anything from, uh, tickets that, uh, clients may have, uh, for questions, problems or whatsoever. To the concept management, to the end user interface and whatsoever. So I think that's really the [00:40:00] position we're taking right now. We're sitting at the middle of the network of people accessing and consuming financial data, and that's ultimately like the main offering we have for, uh, for financial institutions.

I'm hopeful that most of them will probably like unleash the Kraken and turn the switch on before regulations, even though like the date will probably arrive sooner rather than later now. And we actually have big announcements coming up in the next few quarters. But, um, but yeah, like it's. It's not that if it's a when, so I, like, if I had like one advice to banks, it's like, you should do it right now.

And you should actually start with like, probably like, like consumer, there's a lot of upsides, but commercial, I mean, you guys are too big now, but you probably, you probably like. Did some accounting on QuickBooks at some point, like most of SMBs across Canada. Like it sucks. Like it, it really sucks.

QuickBooks or Xero or FreshBooks or whatever the platform, the connectivity behind the scene, [00:41:00] like that's entirely up to the banks to improve that. All of the, all of the other pieces needed to deliver a better experience to their clients are in place. Like it's literally for them to switch, uh, uh, to, to, to switch, uh, from a disgusting experience to a good experience.

And sometime I just, I don't get it. Like why don't they do it? Like why don't they do it? It's, it's literally like, it's actually probably a reason to acquire more commercial, like small business clients. If you have good integration with a lot of accounting platforms, like that's a very high selling argument to me.

Jeff Adamson: I mean, good is the enemy of great. And so I think a lot of the banks kind of just feel like they're doing good enough. And so, you know, what's. You know, when you're like, Hey, we can just make more money doing this over here than we can, than we can by investing in it. And so I think a lot of these things just kind of die on the vine, because when you're already making so much money, kind of maintaining the status quo,

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: then

Jeff Adamson: coming, you being the [00:42:00] guy inside of a bank saying, Hey, we should do something different.

Yeah. Everyone's like, okay, that crazy guy, like, let's just leave, let's just kind of ignore him. You did say it's a matter of when, not if. Let's make a coffee bet right now. When do you think phase one of open banking will come into effect? I'll go first. I'm going to say after the next election. That's when I actually think, I don't, I'm pessimistic.

I'm going to say, I'm an optimist, but on this one, I am actually fairly Very pessimistic. I'll say the first quarter after the next election,

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: I would, I would argue that phrase one is, uh, already in market with, uh, the flinks outbound clients, such as, uh, EQ bank, national bank of Canada, ATV, and, uh, all of the other clients we have.

So let's call it the phase two, the regulation driven phase. I, I, I would be quite pessimistic as well after the next election. The thing is like election may actually influence the timeline, right? So I would, I would probably like if I had to pick a date, I would say probably like [00:43:00] 2026, maybe later.

Jeff Adamson: 2026

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: for phase two.

Uh, yeah. Like the regulation driven open banking. The major problem actually is that when there's regulation, the implementation phase will be extremely long. Whether or not the banks are ready today. He, I think regulators have to assume that banks need to build something, which I think the, I think the builder already done.

Right. But that, that doesn't matter. So, yeah, I think we're years from having like, like a similar to UK or Europe. open banking, but I think it's coming. I still think it's coming.

Jeff Adamson: It will come. Uh, and you guys will be instrumental in that. Where can people learn more about Flinks? Where should they go and either follow you or, or learn more about if Flinks is a good fit for them?

I mean, flinks.

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: com, but, uh, I'm always open to, uh, getting some emails, grabbing a virtual coffee as well. YG at flinks. com, happy to share my email, write me and we'll book some time if you want.

Jeff Adamson: If, uh, if you want the SAS sales reps are furiously writing down your email right now, getting [00:44:00] those drip marketing campaigns ready to go to, to hammer you.

The good thing

Yves-Gabriel Leboeuf: is your podcast probably popular then. So

Jeff Adamson: listen, I, I appreciate you. I appreciate what you're doing for entrepreneurship, the tech community in Canada for bank for banking in Canada. I think it's amazing. Uh, and super grateful for you taking the time to hop on the show. Thanks for inviting me.

Thank you for tuning into behind the brand. If you enjoyed today's show, please subscribe and leave a review on your preferred podcast platform. If you're interested in learning more about Neo Financial, visit us at neofinancial. com. Behind the brand is production of Neo Financial and Media Lab YYC, hosted by me, Jeff Adamson.

Strategy, research, and production by Philippe Burns, Dario Boettcher, and Kyle [00:45:00] Marshall.